NAFTA and Mexico’s Porcelain Wedding

Download the WEA commentaries issue ›

A wedding anniversary is the celebration of love, trust, partnership, tolerance and tenacity. The order varies for any given year. Paul Sweeney

Twenty years ago, on January 1, 1994, Canada, Mexico and the United States launched the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), the first initiative of its kind signed between an emerging economy and two fully industrialized nations. In these twenty years NAFTA has created the largest, if not exactly free, very open trade area in the world in terms of the total value of its intraregional commerce. It should be recalled that NAFTA was the Oreo topping of the ice cream cone of the radical reforms launched by Mexico since the mid 1980s to shift away from its traditional development agenda of State-led industrialization, import substitution and oil-led boom-bust experience of 1976-82. With NAFTA, the government wanted to fully deepen trade liberalization with its main trading partners and, most important, to guarantee the lock-in of the market reform processes. The assumption was that these reforms cum NAFTA would set the Mexican economy on a path of robust manufacturing export-led growth. The balance of NAFTA for Mexico in its porcelain wedding anniversary is sweet and sour. On the sweet side, with NAFTA Mexico became, and has remained, one of the most open large economies in the world. Non-oil products represent more than 85% of its total exports, an acute contrast to the less than 20% they represented in 1980. Since NAFTA non-oil exports expanded at an average annual rate of 11%, practically doubling their previous pace. Moreover, from 1994-95 to 2008 – just before the international financial crisis – and with the exception of China, no country increased its market share in the world market of export of manufactures more than Mexico. In addition, Mexican exports are to a large extent composed of manufactured goods of high technological content. And this superb export performance has been accompanied by a low and stable inflation and very small fiscal deficit.

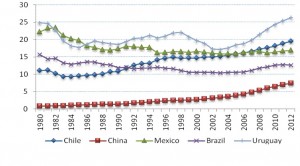

On the sour side, notwithstanding the phenomenal dynamism of exports, the Mexican economy’s strategy these last decades has simply failed in its quest to achieve high and sustained growth. Indeed, while its contribution to world output was 2.68% in 1990 and 2.44% in 1996, it fell steadily since then to reach 2.23% in 2008 and 2.12 in 2013. The growth performance in per capita terms is even more disappointing. Indeed, from 1994 to 2012, Mexico’s GDP per capita, in constant US dollars expanded at a meager annual average rate of 1.1%, a very lackluster result even by Latin American standards, not to mention in comparison with the Mexican economy’s own growth experience in 1950-81. As Figure 1 shows, with such slow growth, Mexico’s gap with the US economy has kept widening since 1982, and the launch of NAFTA did not reverse this adverse trend. Indeed, in 1980 Mexico’s GDP per capita was 23% of the US level, by 1994 the percentage was smaller 17.7%, and 16.9% in 2012. Thus, although since NAFTA the trade position with the US has shifted from massive deficit to a significant surplus, the Mexican economy is lagging behind the US.

Figure 1. Real GDP per capita of Mexico, China, Brazil Chile and Uruguay relative to the United States (percentages, from data in constant US dollars of 2000)

[Source: Author’s elaboration based on data from the World Bank]

With such slow growth, it is not surprising that more than 50% of the Mexican population still live in poverty and informal employment prevails in the labour market.

Given this mixed balance, what is or should be Mexico’s future with NAFTA? Well, to start with, trade liberalization and NAFTA are here to stay. In our view, the obstacles that have blocked Mexico’s economic growth for the last two or three decades are not in its trade policy, except to the extent that it came to fully substitute for industrial policies. NAFTA, as a once beautiful porcelain object, is not broken and, thus, needs not be mended. However, to consider that trade policy and other free trade agreements will be the key tools to push economic growth in Mexico would once again be a severe error.

The obstacles to high and sustained economic growth in Mexico are rooted in other key aspects of the development agenda that it has adopted since the mid 1980s in line with the Washington Consensus. The major one is, perhaps, the belief that has marked macroeconomic policy, namely that low fiscal deficit and low inflations are necessary and sufficient conditions for economic growth. The second one, not unrelated to the previous one, is the weak performance of fixed capital formation. Since the early 1980s, it has been several points below the 25% of GDP threshold identified as the minimum investment ratio required to sustain long-term annual expansions of GDP of 5%. Such weakness is explained by the fact that the contraction in public investment as share of GDP – brought about by the adjustment programs and market reforms commitment to reduce the State’s intervention in the economy – was not fully compensated by a rise in private investment. Thus there is a severe lag of Mexico in public infrastructure and – with the exception of some major national champions – in the modernization of productive plant and equipment vis a vis its international competitors. A third one is the absence of a significant fiscal reform that, with the commitment to keep a zero or very small fiscal deficits, make it even more difficult for the State to expand public investment in the significant volumes that are urgently needed. Finally, after NAFTA, Mexico underwent a major financial liberalization. With most of its domestic banking system being sold to foreign intermediaries, banking credit for productive activities and for investment has been and continues to be severely rationed.

On all these matters, the fiscal and financial reforms recently approved in Mexico seem to move in the right direction. The revival of development banks, the strengthening of fiscal revenues in a more progressive way and the elimination of the by-law fixed zero fiscal deficit are welcome. However, additional fiscal reform is needed to strengthen fiscal performance both on the income and on the expenditure side. And finally, as in most fully developed nations including the US, Great Britain, Japan and Germany, industrial policy has to be reinstated as a legitimate and powerful tool of economic policy in Mexico. Industrial policy is indispensable to achieve the structural transformation of Mexico’s productive apparatus to have more and more robust domestic backward and forward linkages, higher value added in its overall process in export oriented industries as well as in those oriented to the domestic market. The present government has openly admitted the relevance of industrial policy for Mexico today. Whether this revival in the official discourse is flows through to economic policy actions is still not evident. Today, twenty years after NAFTA’s launch, the main focus of Mexico’s economic policy agenda is, funnily enough, very similar to that of the late 1970s: the oil industry. Many actors in the government and the international and local business communities voice their approval of a drastic reform that opens the oil and energy sectors to private, domestic and foreign, investment. In the absence of a renewed and active industrial policy, of another round of fiscal reform to significantly augment tax revenues and public investment, and of strong and efficient regulation authorities of, in particular the energy sector, the claims that energy reform will by itself launch the Mexican economy in a trajectory of high and sustained expansion of 5% per year run the risk of being severely off the mark.

_________________________________

1. Deputy Director and Research Coordinator, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Subregional Headquarters in Mexico. The opinions here expressed are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily coincide with those of ECLAC or of the United Nations Organization.

From: pp.3-4 of World Economics Association Newsletter 3(6), December 2013 http://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/newsletters/Issue3-6.pdf