The political economy of inequality indexes or why the Theil index is, from a political economy point of view, superior to the Gini index.

Download the WEA commentaries issue ›

Would we still try to smell the roses if they had no name at all?

How to map inequality? Which metrics should be used to do this? Economists often use the Gini-index is as the inequality metric of choice. The index clearly is useful. It enables us to calculate standardized rates of inequality of income and wealth which enables historical and international comparisons. Using the size of houses it even proved possible to estimate changes in inequality stretching back thousands of years: “Comparing the size of dwellings at archaeological ruins, researchers found increasing wealth inequality over thousands of years. Technology accelerates the trend, first in the Old World and then in the New. For each site the experts calculated the Gini coefficient”. The index is also routinely calculated and published by organizations like the Worldbank, the OECD and Eurostat. And while the IMF does not seem to publish them, the index is often used in their papers on inequality (look here). The Gini-index clearly enables us to make inequality visible. Inequality is acknowledged, measured and analyzed. A good thing. But: should the Gini-index be the economists’ metric of choice? Below, I will argue that the Gini index has a fundamental flaw while an analytically superior metric exists.

The very nature of the Gini-index obfuscates the social and economic structures and differences underneath inequality. It enables us to look at inequality of society as a whole but it does not enable inequality measurements consistent with an analysis of the political and economic delineations contributing to inequality. To state this differently: when one calculates a Gini index it does matter how many people are rich or poor and how rich or poor they are. But it does not matter if the poor and the rich are laborers, small farmers, CEO’s, black or white or whatever. As such, the index is somewhat related to the ‘representative consumer’ of old style DSGE models. On an analytical meta level inequality is, using the Gini-index, a characteristic of this ‘representative consumer’. It’s a society without social or economic class differences. Or gender or ethnic differences. Or a combination thereof. The difference between the employed and the unemployed does not matter and neither do differences in education. It is, of course, possible to include such differences in the analysis of (changes in) the Gini-index. But such analyses always strike me as somewhat ad-hoc as there is no direct arithmetical or operational relation between (changes in) these explaining variables used and the metric itself. Ideally, when one (using Ricardian framework) looks at differences between landlords and renters or (using a Marxist or, to be more precise, ‘classical’ framework) looking at differences between laborers, capital owners and CEO’s one would like to have a metric which shows the contributions of these analytical ‘variables’ to (changes in) total inequality. The Gini-index excludes such an analysis. Or as an anonymous referee (not for this article) stated, Political Economy:

“had a clear sense of social conflict and stratification and was focused on the distribution of economic product and the surplus; later bastardisation of CPE in the mainstream led to the basic idea that a well-functioning economy is an engine of harmonious growth. Inequality ceases to be a main consideration in this context”.

Branco Milanovic has comparable ideas, relating this to a kind of Zeitgeist:

“Political economy stopped looking at social inequality through the lens of class, which it did from Quesnay through Adam Smith and Ricardo all the way to Marx. It did so precisely around the same time as classical novel disappeared. It was Pareto at the turn of the 20th century who introduced for the first time, studying fiscal data from a number of German and Italian cities and states, interpersonal income inequality. From Pareto onward, we ceased to deal with capitalists, workers, and landlords; we began to deal with individuals, some rich, others poor. The class analysis was definitely pushed out, so much so that in the second half of the 20th century, especially in the United States, even the mention of class in an economic paper would immediately classify you as an unreconstructed Marxist. … It dawned on me that this was not a coincidence: the death of the classical novel, the dissolution of the class structure of the bourgeois society, and the end of a political economy where the subjects were classes in favor of “agents” might have all been related.… But now as the importance of capital incomes increases, and capitalist societies grow increasingly stratified, with the rich attempting to confer and transmit all the advantages to their offspring, may not both the class analysis in economics and the classical novel make a comeback?”

It might be added that the eradication of class and the distribution of wealth from neoclassical economics wasn’t just a question of Zeitgeist but also a deliberate strategy of landowners which subsidized endeavors to eradicate Georgism from intellectual discourse in a fundamental way. In the words of Mason Gaffney: “The stratagem was semantic: to destroy the very words in which he expressed himself.” Inequality, property, land, class – it all disappeared from economic discourse. Using the Gini-index, which disables class or property based arithmetic, fits in such a strategy. It shows the existence of inequality. But it renders the class structure of inequality invisible.

There are alternatives. For one, the Theil index of inequality enables us to change this. Contrary to the Gini-index, the Theil inequality index enables us to directly tie estimates of inequality to the class and ownership structure of a society. As such, it’s an indispensable tool for the political economist, requiring a-priori knowledge of political economic theory but also an inductive reading of the sources and the situation. When one has micro data based on individual households or persons including data on class (or gender or race or all of these) a Theil index can be split into ‘baby-Theils’ (which in their turn can be split into baby-baby Theils…) which show inequality within a particular class as well as between classes. This makes it possible to measure and map the contribution of changes between the size of classes, changes in average income between classes and changes of inequality within classes to (changes in) total Theil-inequality. A proper analysis of course still requires a full-fledged historical analysis of the political history of changes in property relations (look here for historical work by Bas van Bavel and here for a technical description of how to construct such indices by Pedro Conceicaio and James Galbraith). But there are at least precise estimates which have to be explained.

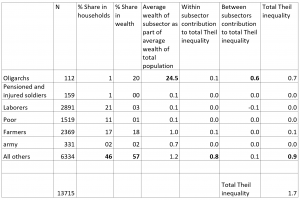

As an example (sorry, I’m an economic historian): a Theil decomposition of wealth inequality in Friesland, 1749, the oligarchs obtaining their wealth from land as well as from political positions based upon land ownership (a quite Ricardian society):

Table 1. A decomposition of Theil inequality for Friesland in 1749 according to socio-economic class.

Source: Knibbe, M. ‘Van Bavel in Friesland. An inquiry into the relation between economic development, measured wealth inequality and the rise of oligarchy in Friesland in the seventeenth and eighteenth century’. In progress.

As can be seen, the 112 ‘oligarchs’ (members of a limited number of families which increasingly monopolized lucrative jobs in the government, including the top of the army) contributed quite a lot to total inequality, partly because of intergroup inequality but to a much larger extent because of the difference between their average wealth and average wealth of the rest of the society. The group ‘all others’ consists of pastors, lots of craftsmen, small and large traders, shell gatherers in coastal cities and the like. Clearly, as the ‘oligarchs’ not only monopolized government jobs but also owned quite some land, this still was a quite Ricardian society. Taking the ‘novel’ approach mentioned by Milanovic: Friesland resembled the countryside as depicted in Great Expectations from Dickens quite a bit, including the fog, cows and the lime kilns and Miss Havisham being a descendant of a family of large traders.

The point: based upon the situation the researcher can specify specific groups (classes, gender, race or even a combination of these) to construct ‘baby-Theils’ which enables a precise measurement of within and between group inequality to total inequality. Ideally, this table should be compared with tables from other periods, mapping changes in inequality and changes in within and between group inequality (hey: work in progress!). This re-introduces class and power in economic analysis, class in this case used in the classical, economic sense. As such, the Theil index is a flexible tool which enables us to move away from single agent models. To do this however requires a thorough and broad knowledge of theory as the researcher has to be able to gauge which specification of the groups not only squares with the questions asked but also with the stratification of the society. But it will enable us to break the bounds of neoclassical economics and return to the political economy roots of the science of economics.

A semantic issue: ‘class’ as used by ‘classical’ economists has clear economic delineations: ‘where does one’s income originate from’. This makes it quite another concept than the ‘bourgeois’ conception of class based upon a mixture of education, your inherited cultural background and occupation and the height as opposed to the origin of your income. Semantics are a thing. Especially in science. Remarkably, the classical distinction, eradicated by neoclassical models, can nowadays also be found in some neoclassical (or should I call these ‘neo-neoclassical’) models, more specific some of the HANK (Heterogenous Agent Neo Keynesian) models which also use capitalists and laborers as classes. Zeitgeist?

From: pp.13-15 of WEA Commentaries 10(4), December 2020

https://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/2020/12/Issue10-4.pdf