Hill – Mankiw 9th Edn Chapter 2: Thinking Like an Economist

Mankiw, N. G. (2021) Principles of macroeconomics (9th ed.)

Principles of microeconomics (9th ed.)

Principles of economics (9th ed.)

Mason, OH: South-Western Cengage Learning.

Rod Hill

University of New Brunswick, Saint John campus

Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada

email: rhill@unb.ca

Chapter 2 – Thinking Like an Economist

Here are some things to consider when reading this chapter on the methodology of economics.

- Applying the Scientific Method in Economics

Mankiw explains that economists, like other scientists, try to dispassionately “devise theories, collect data, and then analyze these data to verify or refute their theories” (p. 17). It would be more precise to say that data, rather than verifying a theory, are consistent with it. More than one theory could be consistent with a particular set of observations. Perhaps more data or better statistical methods would be required to distinguish between competing theories.

How easy is it to refute a theory? A few pages later, Mankiw explains that economists can disagree “because they have different hunches about the validity of alternative theories. Sometimes they disagree because of different judgements about the size of the parameters that measure how economic variables are related” (p. 29). For example, different statistical methods applied to variables measured in slightly different ways can produce a variety of results. Adherents to a particular theory can find a result consistent with their preferred approach. Little wonder the late British-Indian economist Deepak Lal could write: “Ideas – good or bad – never die in economics” (Lal 2000, p. 18).

A final comment. In discussing differences in scientific judgements, Mankiw writes: “Several centuries ago, astronomers debated whether the earth or the sun was at the center of the solar system. More recently, climatologists have debated whether the earth is experiencing global warming and, if so, why. Science is an ongoing search to understand the world around us. It is not surprising that as the search continues, scientists sometimes disagree about the direction in which truth lies” (p. 29, my emphases). The italicized statement is simply false. Almost nothing else about the facts of global warming appears in the book. There are two sentences in Chapter 10: “Moreover, the burning of fossil fuels such as gasoline is widely believed to be the primary cause of global climate change. Experts disagree about how dangerous this threat is, but there is no doubt that the gas tax reduces the threat by discouraging the use of gasoline” (p. 195, my emphases). Three sentences with facts about changing climate appear in a box on carbon taxes on page 198. Given how important this issue is going to be in the lives of today’s students, is this adequate?

- Economic Models and Assumptions in Economic Theory

(i) Assumptions and Model Selection

Because of the complexity of the real world, economic models must make simplifying assumptions which are not true. Mankiw gives the classic example of calculating how long it takes an object to fall from a height, while using the false assumption that it is falling in a vacuum. In some circumstances, this model gives an accurate prediction, so using the false assumption has a negligible effect. In other circumstances – suppose a feather is being dropped – the assumption has a non-negligible effect and a different model, incorporating air resistance, would be needed.

We can say that each model has a particular domain within which it can be applied. This raises a critically important question: what is the domain of applicability of a particular model? We will come back to this question numerous times in these commentaries, because textbook authors typically fail to ask it. Instead, a model is presented as if it is true and can be applied directly to real-world situations without discussion. As a result, another central question goes unasked: which model is most suitable in a certain set of circumstances? Economics does not have a one-size-fits-all model, although introductory economics students could easily come away with that impression.

(ii) Visual Models of the Economy

Chapter 2 presents a simplified model of the economy, the Circular Flow, showing the interactions between households and firms in the markets for goods and services and for factors of production. This model is developed further in the macroeconomics text, adding government, the financial sector and international trade. The details it includes allow certain questions to be addressed.

The features the Circular Flow model omits preclude other questions from being addressed. It sets a framework in students’ minds about how to think about economic life and, just as important, what not to think about.

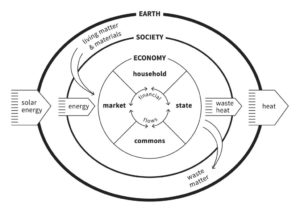

Consider a different model of the economy such as the Embedded Economy model, taken from Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics (2017, Ch.2). This puts the market economy in context. In doing so, it sets an entirely different framework in students’ minds. Different frameworks raise different questions for investigation, so the choice of framework is of central importance.

In one simple picture, the Embedded Economy reminds us that ‘the economy’ also consists of production that takes place within the household, the government sector, and within the commons (i.e. resources which are shared and are not private property). It places economic life in its social context while showing its interaction with the physical world, using energy, living things and materials, while producing waste that is expelled back into the environment. The possibility of global warming is easily seen in the inflow of solar energy and the radiation of heat from the earth system.

Here is an exercise for the reader! Spent a minute thinking about the questions which are not raised by thinking about the economy using the Circular Flow model rather than the Embedded Economy model.

- Positive and Normative Economics

Positive economics attempts to describe the world and the relationship among things in it, e.g. the effects of a particular economic policy on the distribution of income. Normative economics involves ethical or value judgements about different states of the world, e.g. different distributions of income or wealth. In Mankiw’s account, economists wear to different hats: one as scientists doing positive economics, the other as policy advisers doing normative economics. Apparently, they cannot wear both hats at the same time.

Can positive and normative economics be so cleanly separated? We saw in the Commentary to Chapter 1 that the very definition of economics itself, presented as a positive statement, involved implicit normative judgements. The choice of which model to use and what questions to ask (and not to ask), noted in the previous section, involves normative judgements about what is important and what isn’t. The same choices are reflected in the content of the text itself and even in the placement of the topics which are included. For example, income inequality and poverty are examined in Chapter 20, the third to last chapter in the book. Does that reflect a value judgement?

Mankiw writes: “Positive and normative statements are fundamentally different, but within a person’s set of beliefs, they are often intertwined. In particular, positive views about how the world works affect normative views about what policies are desirable… Yet normative conclusions cannot come from positive analysis alone; they involve value judgements as well” (p. 27, my emphasis).

The last sentence is important. It reflects a view in philosophy sometimes called Hume’s Law, named after the 18th century Scottish philosopher (and friend of Adam Smith), David Hume. Positive economic theory never implies a normative conclusion about what economic policy should be. Individuals’ value judgements are required.

- Do economists know which policies are best?

Given the necessity of making value judgements, how can Mankiw write as if there is a unique ‘best’ policy? “Throughout this text, whenever we discuss policy, we often focus on one question: What is the best policy for the government to pursue? We act as if policy were set by a benevolent king” who can figure out the “right policy” (p. 28).

After acknowledging that economists may have different values and therefore differ about what policy should be, he presents a table containing 20 propositions “about which most economists agree”, although they “would fail to command a similar consensus among the public” (p. 30). Half of the propositions are normative statements. If there is widespread agreement among “the experts” about these, then they must share the same value judgements.

Mankiw asks why such policies “persist if the experts are united in their opposition?” He suggests that one possibility “may be that economists have not yet convinced enough of the public that these policies are undesirable. One purpose of this book is to help you understand the economist’s view on these and other subjects and, perhaps, to persuade you that it is the right one” (p. 31).

How can he assert that “the economist’s view… is the right one”? Perhaps he would claim that most economists would agree with the positive economics to be presented in the text and the conclusions would lead any reasonable person to share the same value judgements as the economists.

In effect, Mankiw comes close to saying that the text is an exercise in persuasion. One of the purposes of these commentaries is to help students to read the text critically so they can decide whether or not to be persuaded.

REFERENCES

Lal, Deepak (2000) The Poverty of ‘Development Economics’, MIT Press.

Raworth, Kate (2017) Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think like a 21st-Century Economist, Chelsea Green.

Related commentaries

Birks – Positive and normative