Redefining Governance in Cooperative Banks

Download the WEA commentaries issue ›

By Mitja Stefancic, Silvio Goglio, and Ivana Catturani

Introduction

Recent research shows that the governance of cooperative banks is distinctive; as such, it cannot be adequately captured by using standard economic models (Jones and Kalmi 2015; Jones, Jussila and Kalmi 2016; Paredes-Frigolett, Nachar-Calderón and Marcuello 2016). At the same time, such governance is subject to change. Cooperative banks need to update their governance mechanisms in order to respond to challenges and slacks and in the same way, to avoid losing their specific features. Existing accounts are still incomplete since they are missing important points and so our paper aims to fill this gap.

From the outset, we ask whether the common reference to democracy, often made by cooperative banks’ representatives, is grounded on a solid basis or simply cited for plain marketing purposes. The argument rests on the “one head, one vote” principle. The question therefore is whether this principle promotes true democratic management/governance, even if not clearly defined, or represents a system of governance in which strategic decisions pertain to restricted groups (Klingelhofer 2010).

To assess the kinds of democratic governance mechanisms employed in different types of banks, we focus the discussion on their fundamental characteristics. The goal is to provide a novel discussion on the peculiarities of bank governance, comparing members’ and shareholders’ owned banks by referring to Albert Hirschman’s seminal work Exit, Voice, and Loyalty (1970). Hirschman’s framework is meant to be generic across firms. However, in our case it is important to adapt it by capturing the specifics of cooperative banks to gain a better understanding of their governance mechanisms and to provide proper contextualisation of relevant problems.

An economic model of the discontent of cooperative banks’ members

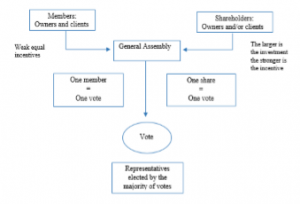

When the banks’ economic performance meets the expectations of both clients and owners (i.e., members or shareholders), the governance mechanisms are straightforward. Figure 1 offers a simple representation.

In joint-stock banks, shareholders with sufficiently large amounts of shares sit in the general assembly and vote to elect their representatives. Smaller shareholders lack the incentives to sit and vote since their decision power is negligible. They implicitly transfer their property rights to larger shareholders whose interests are prominent and whose decisions should increase the value of their shares.

Figure 1: Democratic governance

In cooperative banks, members all have the same (weak) incentives to participate in the general assembly. Their vote has equal weight and should identify those administrators among the individuals of the local community who are able to represent the various interests of the territory.

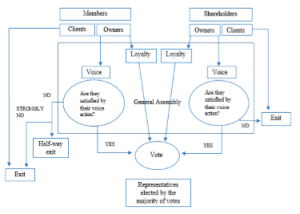

According to Hirschman’s framework, when trust in firms decreases, customers have the possibility to express discontent by either switching firms or voicing their dissatisfaction. Similarly, ordinary customers (i.e., not owners) of both joint-stock and cooperative banks can switch to other banks in cases where they are not pleased with the terms and conditions and services provided by a bank, its performance or general outlook. Matters become more complex when focusing on governance issues.

In joint-stock banks, as in shareholder companies, investors can decide to be loyal and wait for better times, especially when their number of shares is relatively small. Shareholders with stronger incentives might voice their discontent and try to influence the board’s decisions by expressing their views about management at the shareholders’ meetings. Powerful shareholders have the ability to effectively discipline a manager if the latter’s strategies are not viewed as successful enough. Finally, they can sell their shares when the bank performance is below their expectations and their lobby pressure has no impact on the board.

In cooperative banks, shares are usually not tradable (Ferri, Kalmi and Kerola 2015). Instead, the most powerful tool in the hands of members is voice, or “utterance”, to express their eventual dissatisfaction, concerns or disappointment in the bank. In other words, the general assembly is the place where participating members can direct their utterances to the cooperative bank managers and representatives. The problem is to clarify how often this tool is really used by cooperative banks’ members when faced with adverse circumstances.

Several practical limitations are related to the model of governance in cooperative banks, all of which can in some way restrict the efficiency of the utterances of members during the assemblies. For example, cooperative banks’ members may be loyal to their bank, may decide to remain so even during times of distress and may thus be unable to consider switching to another bank. From a theoretical perspective, cooperative values may thus function as deterrents to exiting the bank.

An alternative is that customers switch to different banks yet retain their membership in the cooperative bank. This “half-way exit” is a possibility that is not included in the original version of Hirschman’s framework. Members as clients actually exit from the cooperative banks, while as owners, they become passive. Passive members do not sit in the general assembly, renouncing their property rights. There are various explanations for such behaviour, as follows: (i) Asking for the reimbursement of their shares will not give them any extra profits, especially in times of turmoil when only the actual value of the share can be paid back, not the entire fee. (ii) It is easier to switch back to cooperative banks when the negative period ends (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Democratic governance with “half-way exit” option

“Utterance” might be an alternative when trust in cooperative bank managers and administrators decreases for some reason. However, it should be asked whether utterance is sensibly used to express a member’s own disappointment with the management: utterance may be limited to members who are willing to say something and to those who are able to say something meaningful.

Technically, there can be no true democratic governance unless members are both able and encouraged to voice their dissatisfaction and criticisms towards the management because this is one of the few tools available for cooperative banks to obtain feedback and constructive criticism from their members, which are then useful for updating their strategies and policies. This would also be the way to provide arguments for a change originating within the bank.

Relevance

The most powerful tool for a cooperative bank’s members to express their dissatisfaction is through utterances. To be effective, such a tool requires the members’ strong commitment to monitor the bank managers’ and the bank’s performance. This seems an ongoing problem due to the consolidation process of such banks (e.g., through mergers), at least in the European context. Arguably, the larger the cooperative bank is, the more difficult it becomes to express discontent publicly as the general interest in the bank may decrease among members, with the growth of the latter.

While loyalty and trust should be constantly fostered by cooperative banks, this effort necessarily requires the members’ commitment to the bank itself. Nonetheless, loyalty should under no circumstance preclude the possibility of utterance. Utterance in cooperative banks is essential to contrast the group desire for conformity. An organisation that recognises the positive effects of utterance is able to address the problem of groupthink (Janis, 1982), which can in turn function as a protective mechanism for bank directors and managers, even when problems emerge.

In comparing voice (utterance) with an “art constantly evolving in new directions”, Hirschman (1970, p.12) recognises that voice should be cultivated, promoted, recognised and valued accordingly. This is essentially the task of proficient directors and managers serving the bank. In conclusion, our research suggests further improvements in the framework of democratic governance in cooperative banks by distinguishing between public and private utterance. While private utterance can be used as a tool to secure exemplary banking conditions in any type of bank, public utterance can be more effectively used in cooperative banks.

References

Ferri, G., Kalmi, P. and Kerola, E. (2015). Organizational Structure and Performance in European Banks: A Reassessment. In: A. Kauhanen (Ed.), Advances in the Economic Analysis of Participatory and Labor-Managed Firms (Volume 16). Bingley: Emerald, pp. 109-141.

Hirschman, A.O. (1970). Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Janis, I.L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascoes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Jones, D., Jussila, I. and Kalmi, P. (2016). The Determinants of Membership in Cooperative Banks: Common Bond versus Private Gain, Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, June 2016.

Jones, D. and Kalmi, P. (2015). Membership and Performance in Finnish Financial Cooperatives: A New View of Cooperatives? Review of Social Economy, 73(3): 288-309.

Klingelhofer, J. (2010). Models of Electoral Competition: Three Essays in Political Economics. Stockholm University (Dept. of Economics): Doctoral Dissertation.

Paredes-Frigolett, H., Nachar-Calderón, P. & Marcuello, C. (2016). Modeling the governance of cooperative firms, Computational and Mathematical Organization Theory, 23(1): 122-166.

From: pp.5-8 of WEA Commentaries 8(1), February 2018

https://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/Issue8-1.pdf