Global Rentier Capitalism

Download the WEA commentaries issue ›

Mainstream economics lies in tatters. Certainly, the crash of 2007-08 and the Second Great Depression called into question mainstream macroeconomics, which has failed to provide a convincing explanation of either the causes or consequences of the most severe crisis of capitalism since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

But mainstream microeconomics, too, increasingly appears to be a fantasy—especially when it comes to issues of corporate power.

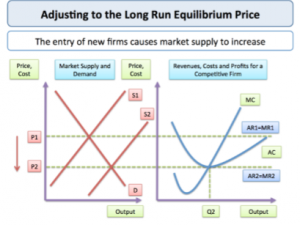

Neoclassical microeconomics is based on a set of models that assume perfect competition. What that means, as my students learned the other day, is that, while in the short run firms may capture super-profits (because price is greater than average total cost, at P1 in the chart above), in the “long run,” with free entry and exit, all those extra-normal profits are competed away (since price is driven down to P2, equal to minimum average total cost). That’s why the long run is such an important concept in neoclassical economic theory. The idea is that, starting with perfect competition, neoclassical economists always end up with. . .perfect competition.1

Except, of course, in the real world, where exactly the opposite has been occurring for the past few decades. Thus, as the authors of the new report from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development have explained, there is a growing concern that

increasing market concentration in leading sectors of the global economy and the growing market and lobbying powers of dominant corporations are creating a new form of global rentier capitalism to the detriment of balanced and inclusive growth for the many.

And they’re not just talking about financial rentier incomes, which has been the focus of attention since the global meltdown provoked by Wall Street nine years ago. Their argument is that a defining feature of “hyperglobalization” is the proliferation of rent-seeking strategies, from technological innovations to mergers and acquisitions, within the non-financial corporate sector. The result is the growth of corporate rents or “surplus profits.”2

As Figure 6.1 shows, the share of surplus profits in total profits grew significantly for all firms both before and after the global financial crisis—from 4 percent during the 1995-2000 period to 19 percent in 2001-2008 and even higher, to 23 percent, in 2009-2015. The top 100 firms (ranked by market capitalization) also saw the growth of their surplus profits, from 16 percent to 30 percent and then, most recently, to 40 percent.3

The analysis suggests both that surplus profits for all firms have grown over time and that there is an ongoing process of bipolarization, with a growing gap between a few high-performing firms and a growing number of low-performing firms.

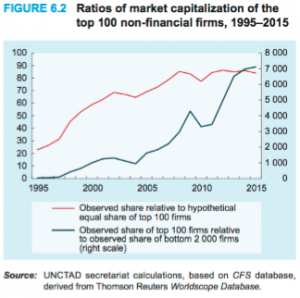

That conclusion is confirmed by their analysis of market concentration, which is presented in Figure 6.2 in terms of the market capitalization of the top 100 nonfinancial firms between 1995 and 2015. The red line shows the actual share of the top 100 firms relative to their hypothetical equal share, assuming that total market capitalization was distributed equally over all firms. The blue line shows the observed share of the top 100 firms relative to the observed share of the bottom 2,000 firms in the sample.

Both measures indicate that the market power of the top companies increased substantially over the 1995-2015 period. For example, the combined share of market capitalization of the top 100 firms was 23 times higher than the share these firms would have held had market capitalization been distributed equally across all firms. By 2015, this gap had increased nearly fourfold, to 84 times. This overall upward surge in concentration, measured by market capitalization since 1995, experienced brief interruptions in 2002−03 after the bursting of the dotcom bubble, and in 2009−2010 in the aftermath of the global financial crisis, and it stabilized at high levels thereafter.4

So, what is causing this growth in market concentration? One reason is because of the nature of the underlying technologies, which involve costs of production that do not rise proportionally to the quantities produced. Instead, after initial high sunk costs (e.g., in the form of expenditures on research and development), the variable costs of producing additional units of output are negligible.5 And then, of course, growing firms can use intellectual property rights and lobbying powers to protect themselves against actual or potential competitors.

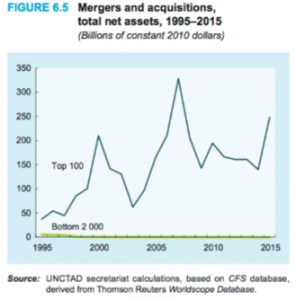

Giant firms can also use their super-profits to merge with and to acquire other firms, a process that has accelerated because—as both a consequence and cause—of the weakening of antitrust legislation and enforcement.

What we’re seeing, then, is a “vicious cycle of underregulation and regulatory capture, on the one hand, and further rampant growth of corporate market power on the other.”

The models of mainstream economics turn out to be a shield, hiding and protecting this strengthening of corporate rule.

What the rest of us, including the folks at UNCTAD, have been witnessing in the real world is the emergence and consolidation of global rentier capitalism.

________________

- There’s another reason why the long run is so important for neoclassical economists. All incomes are presumed to be returns to “factors of production” (e.g., land, labor, and capital), equal to their “marginal products.” But short-run super-profits are a theoretical embarrassment. They represent a return not to any factor of production but to something else: serendipity or Fortuna. Oops! That’s another reason it’s important, within a neoclassical world, for short-run super-profits to be competed away in the long run—to eliminate the existence of returns to the decidedly non-productive factor of luck.

- UNCTAD defines surplus profits as the difference between the estimate of total typical profits and the total of actually observed profits of all firms in the sample in that year. Thus, they end up with a lower estimate of surplus or super-profits than if they’d used a strictly neoclassical definition, which would compare actual profits to a zero-rent (or long-run equilibrium) benchmark.

- The authors note that

these results need to be interpreted with caution. More important than the absolute size of surplus profits for firms in the database in any given sub-period, is their increase over time, in particular the surplus profits of the top 100 firms.

- The authors of the study focus particular attention on the so-called high-tech sector, in which they show “a growing predominance of ‘winner takes most’ superstar firms.”

- Thus, as Piero Sraffa argued long ago, the standard neoclassical model of perfect competition, with U-shaped marginal and average cost curves (i.e., “diminishing returns”), is called into question by increasing returns, with declining marginal and average cost curves.

From: pp.10-13 of WEA Commentaries 7(6), December 2017

https://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/files/Issue7-6.pdf